October 14, 2025 – by Santina Russo

A team of researchers from ETH Zürich has simulated a realistic silicon nanoribbon transistor, for the first time taking into account the interactions between the electrons flowing through it. Their hero runs on the Frontier supercomputer at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and on CSCS’s Alps supercomputer included 42,000 atoms, which represent the largest recorded transistor simulations ever performed at this level of physical complexity. “Until now, simulations of this magnitude, capturing the correlation between electrons in nearly a full transistor structure, were not feasible even with supercomputers—computational demands were simply too high,” said Mathieu Luisier, Professor in the Department of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering at ETH Zürich, who led the work together with Dr. Alexandros N. Ziogas, a research scientist and HPC expert at ETH Zürich. Their achievement earned the team a spot as a finalist for the prestigious Gordon Bell Prize.

What is a nanoribbon transistor?

Transistors are the smallest components of integrated circuits on a chip. They control electrical currents and can act as on/off switches—similar to a light switch, only much smaller. Today’s transistors are ultra-scaled nanoribbons that are stacked on top of each other. Together with other electrical components are critical elements of circuits that perform a wide range of tasks and profoundly affect every aspect of our lives: you already rely on them to wake up in the morning—whether it is your alarm clock or smartwatch—or to surf on the internet with your cell phone. And you depend on countless more during the day. Our everyday life, and nearly every industry and service, runs on chips.

These tiny engines of technological progress have become faster and more powerful mainly because the transistor dimensions keep shrinking. And the more transistors can be packed onto a chip, the greater its performance. State-of-the-art chips currently produced by major vendors like TSMC and Samsung rely on nanoribbon field-effect transistors, about 5 nanometres thick and less than 15 nanometres wide. They will form the core of the newest generation of GPUs, smartphones, laptops, and other electronic devices.

In their work, the ETH Zürich team looked further ahead and simulated future nanoribbon transistors with a height of only 1.5 nanometres, and a width of 5 nanometres. There is a catch at that scale, however: “The smaller the cross section of the nanoribbons, the closer the electrons moving through them come to each other—until electrostatic repulsion between them becomes significant and must be accounted for in the design of these components,” Luisier explained.

From 10 to 42,000 atoms

The so-called GW approximation is widely used in solid-state physics to describe these electron-electron interactions. But it dramatically increases computational cost. That is why scientists could only apply this method to structures comprising much fewer atoms before.

Development started with systems of only tens of atoms and recently reached 2,000 to 3,000 atoms—still far from the size of a realistic system or a full transistor. Now, in 2025, Luisier, Ziogas, and their team joined efforts with Torsten Hoefler, Chief Architect for AI and ML at CSCS, to take another leap forward. They included the GW approximation into a new simulation code, QuaTrEx, and systematically analysed and optimized its computational bottlenecks. Step by step, they improved the code until, for the first time, it could capture the electron-electron interactions in a full nanoribbon transistor, thus including all relevant quantum mechanical effects. This effort earned the team the Gordon Bell Prize nomination.

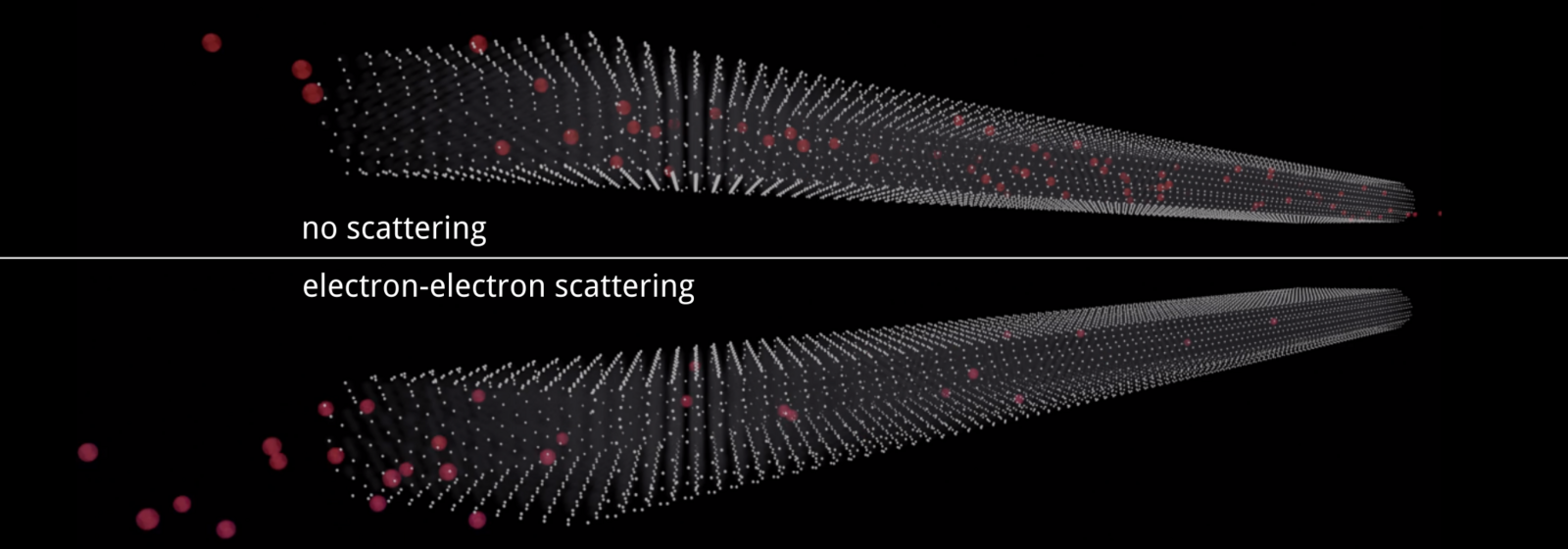

This animation shows the electron transport through a nanoribbon field-effect transistor. When scattering is turned on, as implemented in the QuaTrEx tool, electrons interact with each other, which modifies their trajectories and slows down their motion. In standard models without scattering, electrons follow ballistic trajectories and reach higher velocities. Predictions based on such ballistic simulations are generally overly optimistic.

(Animation: A. Maeder, N. Vetsch)

Notably, while working on the development of QuaTrEx, the scientists discovered how to make optimal use of the supercomputers’ GPU memory. At the same time, they refined the implementation of key computational processes such as the calculation of the boundary conditions that connect the simulation domain with its surroundings, and the solution of sparse linear systems of equations that describe the electron flows.

As a result, the simulations by Luisier, Ziogas, and their colleagues are now about ten times larger than any previous runs using the GW approximation. They included 42,000 atoms in an 86-nanometre-long transistor. In addition, while previous simulations typically ran at 1,000 seconds per iteration, the ETH Zürich team reduced this time to 30 seconds per iteration. “We were able to run these extensive simulations with exaflop performance, which means that our code scales exceptionally well,” said Alexandros Ziogas. Overall, the team improved the simulations’ size, time-to-solution, and performance each by at least one order of magnitude.

Swiss science and supercomputing: competitive worldwide

In a lower-resolution test on CSCS’s Alps supercomputer and with slightly lower computational performance, the team even managed to simulate 84,000 atoms. In this simulation run, their code took advantage of the larger GPU memory available on Alps compared to Frontier.

“We are very happy about the nomination for the Gordon Bell Prize,” said Luisier. This is the second collaboration between Luisier, Ziogas, and Hoefler, who won the Gordon Bell Prize for their then groundbreaking work on heat dissipation in transistors back in 2019.

Luisier and Ziogas see their success as proof that collaboration and persistence matter as much as hardware performance. “For us, this nomination is a motivation to always try to improve—and it shows once again that Swiss science and high-performance computing are competitive worldwide,” Luisier said. Ziogas added: “Supercomputing machines like CSCS’s Alps keep evolving, so there are always exciting opportunities to push the limits.”

Reference:

N. Vetsch et al.: Ab-initio Quantum Transport with the GW Approximation, 42,240 Atoms, and Sustained Exascale Performance, submitted, https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.19138v1