November 19, 2018 - by Barbara Vonarburg

Our Solar System has numerous moons around planets: Apart from Earth and Mars, also Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune and Uranus all have natural satellites. The question is, are moons common even around exoplanets that are orbiting around other stars? “This is an intriguing problem in today’s astronomy, which is hard to answer at the moment,” says Judit Szulágyi, a senior research associate of the University of Zürich and ETH Zürich. The historical discovery of a first exomoon-candidate was just announced in October 2018 by an American group, but the confirmation of this body is still ongoing. With their work now published in the journal “Astrophysical Journal Letters” Judit Szulágyi and her colleagues Marco Cilibrasi and Lucio Mayer both of the University of Zürich are one step closer to solving the mystery of how many exomoons there could be and what they are like.

The researchers focused on the planets Uranus and Neptune in our Solar System, ice giants with almost 20 times the mass of Earth but much smaller than Jupiter and Saturn. Uranus has a system with five major moons. Neptune, on the other hand has only one major, very heavy satellite, Triton.

“It is intriguing that these two very similar planets have completely different moon systems, indicating a very different formation history,” explains Szulágyi. The astrophysicists believe that Triton was captured by Neptune – a relatively rare event. But the moons of Uranus look more like Saturn’s and Jupiter’s systems that are thought to have originated in a gaseous disk around the planets at the end of their formation.

Simulations with supercomputer

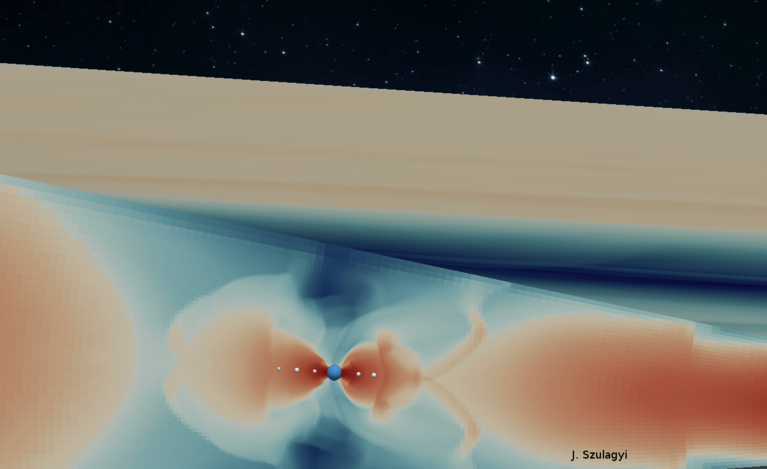

“So far it was believed that Uranus and Neptune are too light to form such a disk,” says the astrophysicist. Therefore, it was considered that the moons of Uranus could have formed after a cosmic collision – like our own moon, also a relatively infrequent event as the capture. Now the researchers who are also members of the NCCR PlanetS were able to refute this previous idea. Their extremely complex computer simulations reveal that in fact Uranus and Neptune were making their own gas-dust disk while they were still forming. The calculations generated icy moons in-situ, that are very similar in composition with the current Uranian satellites. From the simulations performed by the supercomputer at CSCS it is clear that Neptune originally also was orbited by a Uranus-like, multiple moon system, but this must have been wiped out during the capture of Triton.

The new study has a much wider impact on moons in general, than only on our Solar System formation history. “If ice giants can also form their own satellites, that means that the population of moons in the Universe is much more abundant than previously thought,” summarizes Szulágyi. Ice giants and mini-Neptune planets are often discovered by exoplanet surveys, so this planet mass category is very frequent. “We can therefore expect many more exomoon discoveries in the next decade,” the astrophysicist says.

This finding is also extremely exciting in the view of searching for habitable worlds. In our Solar System, the two main targets to search for extraterrestrial life are icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn: Europa and Enceladus. They both are thought to harbor liquid water oceans below their thick ice crust. “Those under-surface oceans are obvious places where life as we know could potentially develop,” says Judit Szulágyi: “So a much larger population of icy moons in the Universe means more potentially habitable worlds out there than it was imagined so far. They will be excellent targets to search for life outside the Solar System.”

At the beginning of the animation planets form in gas-dust disks around young stars. Then we see a forming planet vicinity, a disk formed around the nascent planet, where its moons born (brown spheres). Ice giants (Uranus and Neptune) were forming their moons in such a disk, similarly to gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn). Credits: animation created by S. Dobler, from the simulation done by J. Szulagyi (UZH/ETH).

Reference:

Szulágyi J, Cilibrasi M and Mayer L: In situ formation of icy moons of Uranus and Neptune, 2018, ApJL, 868, L13 DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/aaeed6